I was recently interviewed by Joshua Sheats for the Radical Personal Finance podcast. Josh is a CFP with a solid understanding of general finance (and incredibly personable to boot). He is also very cautious towards peer to peer lending, and this becomes quickly apparent if you listen to the interview. The phrase he kept repeating was, “It will be interesting to see what happens” or “I’m looking forward to how this pans out.”

Lending Club and Prosper’s Thin Historical Performance

The fact is, Josh is voicing a very typical concern for the average American investor. Despite Lending Club and Prosper having years of positive returns, consistent growth, and celebratory coverage in major press, the general picture just does not leave him convinced. His solution to this critique is to give peer to peer lending more time. This current success needs to continue for decades before Josh would seriously consider jumping in with both feet.

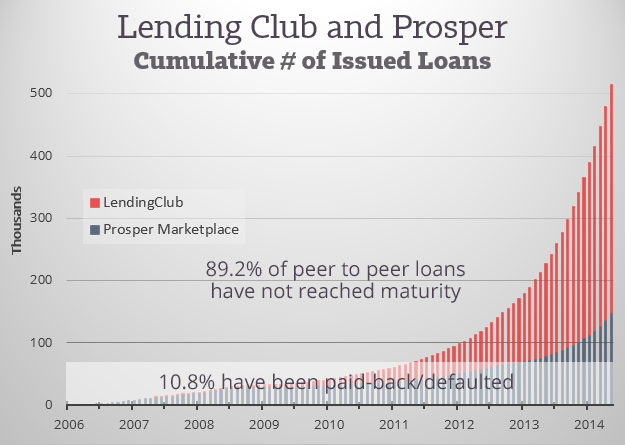

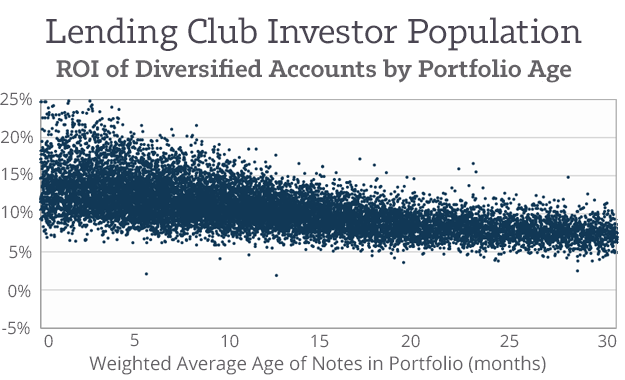

Here’s a chart that demonstrates where Josh is coming from:

Despite record-breaking success month-over-month, just a tenth of the loans these platforms have issued have hit maturity. Overall, the dataset is very young and incomplete. In a certain light, peer to peer lending is indeed an unproven investment.

A good solution of this problem is, like Josh said, to simply give it more time. Ten years from now, all of these hundreds of thousands of 3-year and 5-year loans we’re issuing today will have been paid back or defaulted, so we will then be in a better place to judge this investment’s worth.

But peer to peer lending is not a new investment

Unfortunately, what many investors do not realize is how peer to peer lending is not actually that new or unfamiliar to American finance. It is actually part of a very proven asset class called prime consumer credit. And while Lending Club and Prosper have a very young dataset between them, consumer credit has decades of open data we can examine, specifically the money that major banks have made off credit cards.

Credit cards are the same kind of investment as a peer to peer loan, something that people like Brendan Ross have been touting for years. Both are simply a line of credit given to creditworthy individual Americans. Both are part of the ‘consumer credit’ asset class. And if we examine the historical performance of credit cards, we get a picture for how peer to peer lending may perform in the coming decades.

Why Banks Stuff Your Mailbox with Credit Card Offers

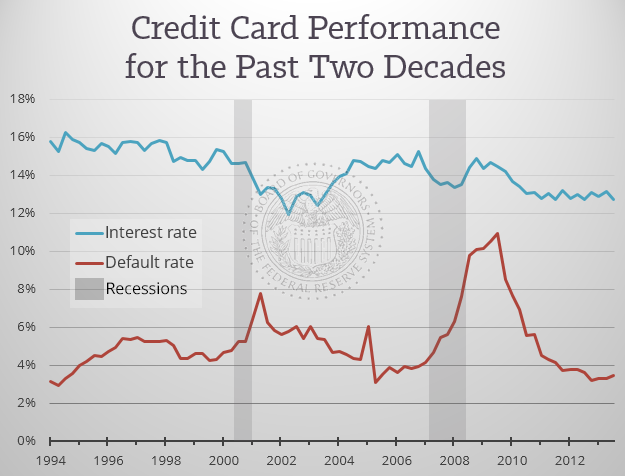

We can examine credit card performance via the Federal Reserve website. Since the government requires the issuers to publicly state the interest and default rates of their credit cards, we can download the data and figure out the return the banks have been earning. What does it show? For decades the banks have earned scads of money by issuing these lines of credit:

See the wide spread between the blue and red line? That, my friends, is the lucrative yield that the banks earned by lending money to responsible individuals.

Of course, this picture does not show the operating expenses of these issuers (how much they had to spend hunting down prospects, getting them approved, manufacturing and sending out the little plastic cards, servicing their accounts, and collecting bad debts), but the spread is nevertheless an incredible thing to look at.

Peer to peer lending allows us to join the party

For the first time in history, the internet has allowed average people to partake in this incredible asset class.

“This is the first time in history that non-bank investors can get access to unsecured consumer-credit products.” Aaron Vermut, CEO of Prosper (The Economist)

This is why peer to peer lending is amazing. Yes, this investment is socially responsible for the way it is getting people out of debt; and yes, the way it operates through low-cost cutting-edge technology is remarkable. However, the reason peer to peer lending really shines against traditional investments is for how it allows us access to the awesome asset class of consumer credit. This is what makes it a big deal. This is what gives it such great and consistent returns year after year.

The Lost Decade: Stock Market Investing in the 2000s

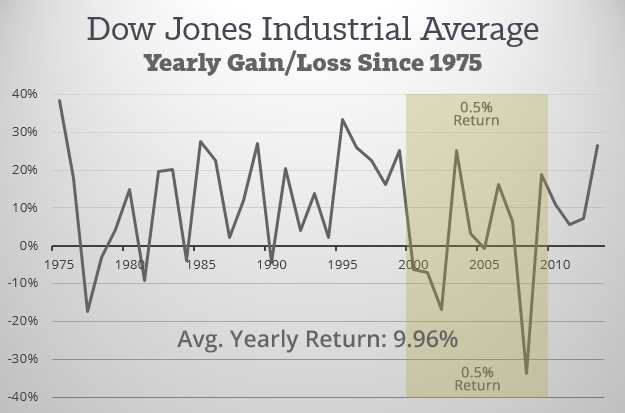

To really hammer this point home, here’s a chart that shows the amount investors earned per year on the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), which is an index that many look to as a representation of the stock market as a whole:

The first thing to notice is how wild and jagged this line is. Some years it rose 20%, other years it dropped 10%. This is the volatility of the DJIA. Overall though, it is worth noting how it has garnered investors a great 10% return since 1975.

The ugly importance of timing the market

What sours this return is the yellow area, which is the ten-year span of 2000-2010. During this period, the stock market returned about 0.5% to investors, which many now refer to as a lost decade (Wall Street Journal). If you were a fresh graduate from college in 2000, and you jumped headfirst into those higher-risk retirement plans they set aside for new investors, you likely had a pretty rough opinion of stock market investing by the time 2010 rolled around. Yes, the market has earned investors 12% per year since then, but if we include the 2000s, this average drops to just 4% per year.

In stock market investing, timing matters a great deal.

The point I’m trying to make here is that in stock market investing, timing matters a great deal. If you were a new investor in the 1990s, you’re probably pretty happy with 16% returns per year. But if you were a new investor in the 2000s, you took on a lot of risk and earned nothing at all. People starting to save for retirement for the first time in their lives often get anxious trying to figure out how the next 10 years will perform. Yes, the market has historically returned 10% per year, but tell that to college grads of 2000.

Furthermore, many of the newly hired are required to figure this stuff out. Many of my friends in their 20s and 30s have to self-start their retirement accounts because their employer no longer offers pension options. And when they look at volatile charts like the DJIA 40-year above, they feel nervous about how to begin.

Prime Consumer Credit Has No Lost Decade

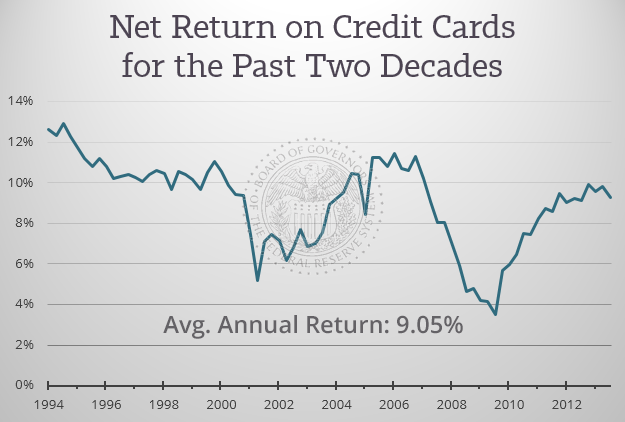

Heck, it doesn’t even have a lost year if we focus on credit cards. Here is the net return the banks earned on issuing credit to people for the past twenty years (interest rates minus default rates):

Consumer credit has at least twenty straight years of positive returns. It probably has many more decades, but the Federal Reserve only provides figures going back to 1994. Long charts show the interest rates remaining healthy for forty or fifty years running.

At no point in recent history have banks lost money on credit cards.

The best part of the above chart is how the blue line never touches the bottom. At no point in recent history have banks lost money on credit cards. Even in the ugly economic environment of 2008 the banks likely earned 2-3%, which is strikingly similar to what Lending Club returned their investors. This is even more amazing when compared to the stock market. In 2008 the DJIA lost investors a staggering 33%, and has on average crossed into negative returns every fourth year since 1975.

When it comes to my own personal retirement, I have to put it in the hands of the most trustworthy investment I can find. If I do this wrong, I have to remain employed into my eighties. With that fact in mind, I just don’t feel comfortable centering my investment on the stock market.

Consumer Credit is an Awesome Investment

What I do feel comfortable with is entrusting my cash to responsible American individuals, which is the foundation of peer to peer lending. As the charts above show, people with good credit are easily one of the most stable and rewarding investments available. The problem is, like Joshua Sheats communicated, that most people see lending money online to total strangers as something highly risky and speculative.

But peer to peer lending is not highly speculative. Yes, there are definite risks to consider like platform bankruptcy and regulatory burdens, but at the end of the day it is a way of investing that our nation has actually practiced for decades, and with great results — it is just unfamiliar because it’s been the privilege of major banks.

The question I would ask the new American investor is this: do you want a rocky investment that may earn you 10% per year, but has a history of losing entire decades? Or do you want a simple and stable investment that still offers historical returns of 7% per year, and has never had a down year?

Great article Simon, thanks! Enjoyed your interview on RPF podcast as well as this expanded explanation.

Thanks Greg. Glad you liked the interview.

The low volatility of p2p lending is the main argument I make with friends who dismiss it as something novel. Thanks for painting it clearly in this article.

You’re welcome Nate.

Well done Simon. Nice answer to a very common question.

I would like to see the see the credit card and Dow Jones graphs on one chart.

Thanks Jason. I’ll see what I can come up with and get in touch with you via email.

Simon,

Kudos to you for putting this article together! Very insightful.

As you know, I have been an advocate of P2P or marketplace lending since 2008. Back then the stock market tanked and yet my P2P funds still eked out a 3% return which was the only positive return I had out of my investment vehicles.

I agree that proper filtering and continuous investment into this market will yield positive returns year in and year out.

Thanks Jack. Your experience in 2008 is a story that needs to be shouted from the rooftops.

I am a great fan of p2p lending. I am currently unable to invest in it as an Italian resident, and i hope that LendingClub allows me to do so in the future. That said, I think this article is a bit dishonest.

1) P2p lending should be compared to bonds, not to an equity investment.

2) The DJIA is a joke of an index (price weighted, not representative of the US economy of late, etc). You should have used the SP500.

3) You should have used a TOTAL RETURN index. Dividends aren’t included in your analysis

4) When analyzing the returns of somebody building his pension pot, you shouldn’t do it the same way you would for a lump sum invested. What I mean is that you should have tracked an equity portfolio that gets regular contributions every year (savings).

5) Equities are a mandatory part of any pension pot according to any financial advisor you would talk with, especially in the accumulation phase (before your fifties).

6) P2p at the current time isn’t practical at all if you want to invest considerable sums. Given that a pension pot can (should!) run into the hundreds of thousands of USD, even the most ardent p2p lender will find it (for the time being) difficult to allocate more than $ 30-40k into notes. Good luck trying to manage the continuous re-investment of interst + principal returned, selling the defaulting notes and so on, with 100k on LendingClub.

My opinion is that this article does a good job at explaining that p2p lending isn’t a new asset class. It also does a good job in pointing out that it’s very probable that annual returns from it will be positive almost every year in the future. But the correct role that p2p lending should take in a pension pot is that of high yield bonds. A decent part of your portfolios should be in bonds anyway, and p2p can be the star there. Just don’t avoid equities for the long term, because that would be extremely detrimental for your financial well-being.

Hi Lucio,

Thank you for your well written comment. I can see you’re quite proficient in the wider financial world, so your points give me much to think about.

My thoughts:

1) As to whether p2p should be classified as fixed-income is up for debate. I agree that’s the most likely bucket, but it doesn’t really have the liquidity of a bond investment.

2) I used the DJIA bc it’s the most popular. But the S&P would have sufficed. The three metrics I cited are comparable (the SP500 is @ -0.6% for 2000s).

3) I probably should have included dividends. That said, if authorities like the WSJ are calling the 2000s a lost decade, doing this should not have changed things too much.

4) See #3. Regular contributions are certainly best practice. But the decade was lost anyways.

5) I understand it is traditionally best-practice to include equities. However, I actually know a few major RIAs who manage huge New York clients, and they would say this conventional wisdom is being challenged by marketplace lending. This topic is beyond the scope of my post though. My point is the consistent yield of prime consumer credit.

6) I actually know many people who invest hundreds of thousands of dollars via Lending Club without hassle. Reinvestment is fine, and getting easier each year. Selling notes (liquidity) is a real hassle at that scale though, so for them it’s typically buy-and-hold. Hmm, sounds like retirement :).

First to Simon Cunningham: brilliant article. I had never considered it in the wider historical context, and believe you are right on track with your analysis. I think this article will let many people sleep a little better at night.

Lucio Martelli,

Your points 1-4 are probably all valid. They are ultimately just quibbles, because they don’t affect the final conclusion of this article. But it’s good you brought them up. However, on point number five, I think the gist of what you’re saying is misleading. And on point number six, you are just flat-out incorrect.

On point number five, you said: “Equities are a mandatory part of any pension pot according to any financial advisor you would talk with, especially in the accumulation phase (before your fifties).”

Financial advisors over the years have advised many things, some of which have been later proven to be misleading, incorrect, or flat out destructive. Most of the portfolio allocation rules of thumb were based on Modern Portfolio Theory (which is not really modern, being created in the 50s). The recent financial crisis, showed that many of the assumptions this was based on were severely flawed.Few of the “big boys” (institutional investors) follow the old rules, and now the consensus is scattered across numerous new theories (Post modern portfolio theory, Monte Carlo simulations, etc.). However, the old theories were much easier to explain, so most financial planners haven’t changed their marketing pitches to clients.

I’m not saying that stocks don’t belong in many if not most portfolios. And I’m not saying that investors who aren’t fully knowledgeable, shouldn’t seek out the advice of others. I am saying that when things go bad, you’re the one losing your money: not your financial advisor. Times change, and rules of thumb need to stay updated with the current times, or they can be dangerous.

On number six you said:

“P2p at the current time isn’t practical at all if you want to invest considerable sums. Given that a pension pot can (should!) run into the hundreds of thousands of USD, even the most ardent p2p lender will find it (for the time being) difficult to allocate more than $ 30-40k into notes. Good luck trying to manage the continuous re-investment of interst + principal returned, selling the defaulting notes and so on, with 100k on LendingClub.”

This is flat-out incorrect. I have a few hundred thousand invested in P2P, and it’s effortless actually. Lendingclub has absorbed the entire amount into notes. I just set it on automatic investing and no effort required whatsoever. There are many institutional investors who invest far more than I do.

I’d suggest that since you’ve never used the lendingclub, you’re probably not the most authoritative source to talk about its limitations. ;-)

Excellent article and very well written. I would argue though that this asset class has had positive net returns for much longer than 20 years. Although your charts begin with 1994, banks have earned a positive lending spread on consumer credit for much longer. P2P Lending is simply old school banking done through the Internet. As with any asset class, it’s often how you manage it that determines the risk. If you use a high degree of leverage in lower quality paper, then risks could be very high. However, if you have a well diversified portfolio of prime paper that is unlevered, then most would agree this would be very low risk and could maintain positive returns through all phases of the business cycle.

Thanks Don. Excellent points.

Something you failed to mention is that ETFs and stocks receive favorable tax treatment if you hold for at least one year. There is a substantial difference between the ordinary income rate and the long-term cap gains rate

Great point. Thanks Adam.

Great article Simon, Always enjoy your commentaries.

As an investor since 2009, I too, having started on a very tiny scale, am still amazed, and encouraged, as I forge ahead, at the actual end of day positive returns of this space.

Having always wanted to participate in the credit card returns in past years, as the average investor, one was barred thru direct investments due to their 1-10Million $’s needed to go direct purchase on these types of instruments.

Thru the vehicles now available, one may participate with as little as 25$, if one wants to test the market, yet, advocate a diversified portfolio of approx 400 loans min, per the wisdom out there, being correct, to diversify risk fully, and leave chance behind.

As to ordinary gains, vs a better tax structure, wondering if anyone out there has heard of a scenario a CPA proposed, which sets up a “investment structure”, for ones’ own use only, thus being able to deduct a lot of items, and paying taxes on net gains, perhaps at a much lower rate as if distributions are not made form the vehicle on a short term basis?

Keep up the great work, and yes, everyone that has some free funds should definitely look into this space to take advantage of pretty consistent returns, as you amply demonstrate in your excellent post. Thank you, as always for your insightful and elucidating commentary.

Simon, here’s another thought. Do you know if the credit card consumer market referenced in those graphs is truly the same as Lendingclub’s market of prime borrowers?

I’ve heard stories of people with questionable credit receiving credit cards in the mail. If those kinds of people are included in the graph, then an argument can be made that Lending Club’s borrowers might be significantly better then the typical credit card company, If so, it could be expected to perform better than even the very good results shown above, during a downturn.

Thanks for the kind words, Ian. I do not know the hard FICO threshold behind credit card issuance. That said, people much smarter than myself continue to hold both p2p lending and credit card issuance as the same asset class: prime-rated consumer credit.

Surely there are bad borrowers in both buckets, but the populations seem comparable to me as well. But as to your question about who would perform better in a downturn, I wouldn’t necessarily say Lending Club would. While their account’s aren’t revolving lines of debt (which lowers default rates), their underwriting is likely less refined than credit cards. They haven’t really experienced a full recession, unlike credit card issuers have done many times.

All in all, it remains to be seen how these compare. But I stand by this article in saying that both credit cards and p2p loans seem the same type of investment, and both are more consistent in tough economic times than equity investments like stocks. Or perhaps even bond investments (which have had many negative years).